- Home

- Product

- Refrigerated Air Dryer

- Adsorption Dryer (Double Tower Type)

- Combined Low Dew Point Compressed Air Dryer

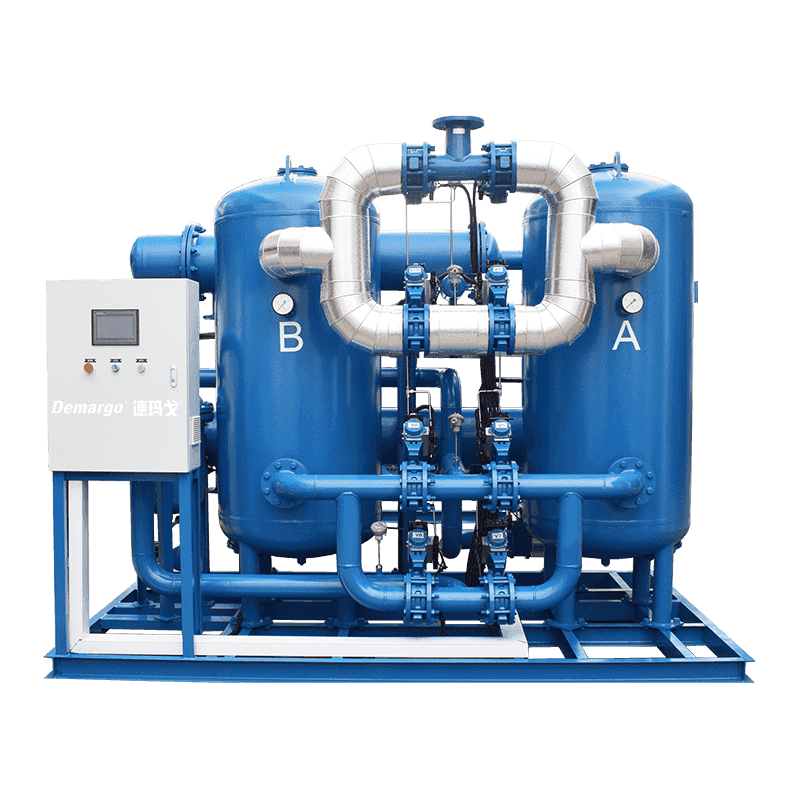

- Compression Heat Regeneration Adsorption Dryer

- Micro Air Consumption, Zero Air Consumption Blast Heat Regeneration Dryer

- Module/Mold Core Dryer

- Special Gas Dryer

- Compressed Air Filter

- Stainless Steel Compressed Air Filter

- High Efficiency Oil Remover

- Waste Oil Collector/Condensate/Condensate Treatment Separator

- Oil Water Separator

- Drainage Type

- Explosion-Proof Dryer

- About

- Application

- Case

- Support

- News

- Contact

INQUIRE NOW